Via Art&Education

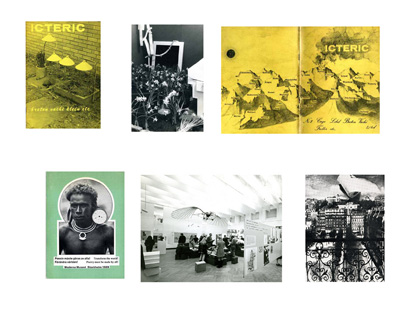

‘Icteric’ was the name adopted by a radical arts group and magazine operating in Newcastle around 1967. ‘Icteric’ can be seen as an avant-garde group who knew ‘how to use’ earlier avant-gardes, and then, in true avant-garde fashion, actively participate in its own dissolution. We are dealing with a confluence of – abandonment, suicide and suppression. One outgrowth of ‘Icteric’ (meaning both jaundiced and a cure for jaundice) was the exhibition ‘Poetry must be made by all / Transform the World ‘ which I curated for the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 1969. ‘ Poetry must be made by all…’ attempted to bring to light that prefiguration of the supercession of art – hinted at by the 20’s avant-gardes and tantalisingly glimpsed in the heady days of May ’68. The exhibition’s rather odd history – acclaim: suppression : neglect – concluded with its disappearance in Canada in 1972.

Forty years on seems a safe time for a little nostalgia. In a time of accelerating recuperation / co-option and the ‘fall’ of the modern, it may be worth recalling the move of a handful of people from being part of the modernist art scene to a position of anti- modernism and anti-art, whose refusal of recuperation has led to near invisibility. To do this is to acknowledge that such nostalgia can only help return this moment to the fold it so vigorously rejected.

Arriving in Newcastle in 1963 to take up the position of Librarian in the University Fine Art Department was a somewhat conflicted experience. I wanted to work in an art school – to see ‘art in the making’. But ‘modern art’ was for me already the site of some disillusion. I had been ‘devilling’ for Sir Herbert Read for some two years on the modern section of Kindler’s Malerei Lexicon, this while working as a Library Assistant in the V &A. Such exposure had left me with a good deal of scepticism.

I was in Newcastle at the instigation of Richard Hamilton, whom I had met partly through an interest in Duchamp – then (1962) something of a peripheral figure. The more I worked on the mainstream: the more the periphery interested me. That periphery being defined by Dada and the Russian avant-garde – both, then, appearing as an alternative to orthodox modernism. In Newcastle my interest focussed on Picabia; and at Richard Hamilton’s suggestion I curated a Picabia show seen at the Hatton and the ICA in 1964. This led to writing for Artforum. Richard was of course working on the reconstruction of the ‘Large Glass’ – so the ground in Newcastle was prepared for the reception of related work. I sat in the Library pushing Dada, the Surrealism of the ‘lived’, and other peripheral material (i.e. late Constructivism) to any student with a deviant strain.

This was the time of the first happenings and the critique of art as object. In short the grounds for the rejection of art as commodity were being unearthed.

Among those receptive to the ‘new tremors (that) are running through the atmosphere’ were twin brothers David and Stuart Wise. They were part of a mini-dynasty – Derwent, a Lecturer in Sculpture in the Department – and Douglas, some 50 yards away – a Lecturer in Architecture. The path of their elder brothers was emphatically not one they were going to follow – though Stuart was Studio Demonstrator in 1966- 67. They shared my interests and we started meeting regularly discussing ways of moving on – beyond the established trajectory of modernism.

At this stage they were working on installations (though the word was many years away), of a pretty ephemeral nature. Some of these involved toy trains, butterflies etc. They believed – like Breton – in ‘reliving in exaltation the best moments of childhood.’ Already there was a real sense of movement – perhaps enhanced by the fact that they were no longer students yoked to the attainment of a degree – a momentum so powerful that it was impossible to think they might still be making such things in 6 months time. Childhood existed – strangely enough – with a preoccupation with death. Both would soon be brought into play. Also involved was John Myers – a final year student, and Trevor Winkfield who had just finished being ‘self-taught as a painter’ at the R.C.A., he had come to visit and talk about the same things gripping us. Thus there were 5 people all fascinated by the radicalism of the 20s, but all acutely aware of the current scene – from Fluxus to Minimalism; though these exerted little of the pull of the other. Also of interest was the whole field of art rejected by the art ‘police’. Trevor had come to lecture on de Chirico – the later and then reviled de Chirico. When Quentin Bell visited to lecture on “Bad Art”- we were – perversely – bowled over by his examples of the ‘bad’ e.g. Soviet Socialist Realism. All this then spelled a growing commitment to so-called anti-art.

If I had slipped into identifying with the peripheral and anti-art current over a period of several years, then the others – notably the Wises – followed the same course in a matter of months. I think identifying is the right word here. As regards the 20s this was not history, i.e. something that had occurred forty years earlier; this was something to be used as a current source of inspiration. And there was a surprisingly large cache of it to be resuscitated. We used it as others might use landscape or Tamla Motown. As for the 60s much of it seemed right for parody, for detournement (though we had yet to discover the Situationists).

(I think it is not without interest that in the 60’s Dada and Surrealism, and Constructivism to a lesser extent, were areas that were mainly of interest to artists, not art historians. (I learned much of Duchamp from Hamilton, much of Picabia from Lebel, much of Magritte from Patrick Hughes, of de Cririco from Trevor Winkfield and much of Malevich from Anthony Hill).

Why were we so concerned with the periphery – with an anti-art current ? The periphery -( lets say for Constructivism – film, Blue Blouse, Worker correspondents, for Dada – the Barres Trial, for Surrealism – the stickers, the Centrale etc. all areas generally ignored in favour of the art object ) – seemed less institutionalised, often nearer the everyday, and seemed to enjoy a friction with other areas of activity . Clearly this concern on our part was in itself also a vanguard thing. This was also the time when institutionalisation began to bite: Duchamp was ensconced in the Tate; the American Pop artists were the first generation of jet setting super stars; there was an emerging critique of art as object. And for us in Newcastle – all more or less from working class backgrounds – there was the snobbery attached to the University Fine Art Department – the old boy network etc. Something that was to surface with Richard Hamilton’s departure.

We soon moved to the idea of a collective and magazine. We needed a name and found it by utilising the precedent of Dada i.e. by opening a dictionary at random. There my finger alighted on icteric – meaning jaundiced and a cure for jaundice. Undoubtedly a happy accident; a kind of objective chance. We took on board much of the anti-art aesthetic – the jaundiced; but also the idea of the curative; thus we could indulge the luxury of continuing to make art. Though like much else at the time this was pretty unclassifiable by the older standards of art. Did we think of ourselves as an avant-garde? I’m not sure, but we were seduced by the idea of the avant-garde, There was something undeniably romantic about the whole historical vanguard project. Consequently we were unable to see its fundamental contradictions – only later understanding its role in sustaining the culture it attacked.

Early activities included putting on stage the letters I.C.T.E.R.I.C behind Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry playing in Newcastle. John Myers arranged a reading/shouting of Tzara’s Roar for about 200 people in a car park. Trevor Winkfield, a Satie admirer, came to give a piano recital; he’d never touched a piano before, but this did not deter him from carrying it off with aplomb. We also gave a lecture/performance on hearing of Breton’s death.

The first issue of the magazine came out in late ’66, ‘Published for the Fine Art Society by Icteric’. The Fine Art Society was quite important – highly responsive to our suggestions. They financed Trevor’s visits – as well as those of the sympathetic wing at Leeds – Patrick Hughes, Robin Page etc. They also ran a film programme – much of it again requested by us – e.g. Flaherty, Bunuel, Eisenstein and Vertov; (as I remember it ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ hadn’t been out of the BFI for over a decade).

The magazine cover (Fig 1) featured a ‘sculpture’ by the Wises. As a work it crossed boundaries. It was aesthetic, but useful – it functioned at night to illuminate the path to my back door. It had sculptural elements – the mole and trough were fibreglass, but also elements that grew – the grass and bush needed cutting. They also contributed a text ‘Notes on Butterflies’ – a genre which in the context of an arts magazine was, to say the least, idiosyncratic and provocative. There were sculptures by John Myers – including a fish pond in perspex, which had a lawn, and gestured obliquely – as did a series of 30 inch high white spheres in an irregular grid on a tennis court – to minimalism. Trevor Winkfield was represented by a sculpture – a plaster model of his home in Leeds, covered in paint a la Pollock – and a poem. My contribution was an interview with Rotraut – Yves Klein’s widow. (I’d just published an article on Klein in Artforum. For me, at the time, Klein belonged to the periphery – that was soon to change. Perhaps the most important ‘scoop’ was Anne Ryder’s translation of the first half of Vache’s ‘War Letters’, with Breton’s Introductions. No other translation into English was to appear for over a decade. Cited approvingly on the rear cover were Meyerhold, Robert Smithson – we liked his deadpan wit, and Heraclitus – “Even the sacred barley drink separates when it is not stirred”.

Following the first issue we put on a collaborative effort – an ‘ Event’ as we then termed it – based around a line from Rimbaud (a ‘deserter’ in Lebel’s terms) and a photograph of Malevich ‘lying in state’ This was ‘’Why not indeed toys, incense and death’ – (Fig 2), the word death being added to a line from Rimbaud’s – Illuminations – XII. The photo of Malevich had recently been published by Troels Andersen in a Moderna Museet catalogue. As a group we were already great admirers – the photo of Malevich in the coffin – a kind of real architekton -only confirmed our enthusiasm. David rebuilt the coffin and we had a room for a week. Listing the elements may bring out something of its originality :

A background on three sides of panels covered in red felt // A synthetic grass floor // A replica of the Black Square // daffodils in jars and petrie dishes // Plastic daffodils // A row of bricks (referred to as our Carl Andre) // A toy train shunting up and down by the coffin // A light fitting tied up in foam rubber which reached to the floor ( a ‘gesture’ to eccentric abstraction) // Beethoven’s Rasumovsky quartet. // Incense.(fig.7).The elements were rearranged continually.

Also, for an hour each evening , one of the group lay in the coffin while the others stood in the position of Suetin and other Suprematists in the original photo. Various actions could take place. When Trevor Winkfield was in the coffin I walked over and put my foot through the ‘Black Square;’ Trevor- far away – he’d been there about 45 minutes – thought the apocalypse had arrived . It seemed to easily bridge the years 1935 and 1967. It was beautiful and absurd, (but wasn’t death absurd as Vache had said and shown? Fig (2)

Just why we were preoccupied with death is hard to say. Maybe Malevich had somehow proved it utterly desirable. And, it must be remembered that most of our mentors were dead – several by their own hands. ‘Art is dead’ was a slogan heard increasingly from various disaffected quarters. The third issue of the magazine was to be thematic – on Death – we gathered

The second issue of the magazine came out in June ’67. The cover – like the first a jaundiced yellow – showed a mountain range with the names of our ‘heroes’ scattered across it (Fig.3). Breton’s name on high astride a volcano. The other names showed that eclectic purview that was to be so important to us. There were plenty of Russians – Blue Blouse, Feks, Arvatov, Khlebnikov, etc. Various Dadas including -by proxy -Woynow who was with Vache when he died, Charlie Parker ‘ for dying of laughter’ ; Sherman ‘for evading his followers’ -(Sherman was a John Myers invention.); de Chirico ‘for his diatribes against modern art’ etc. etc.. I doubt if many readers would have recognised the majority of names. In several ways it was a more substantial affair than the first. We were still unabashedly putting ourselves forward. Stuart this time had a piece on slugs, with some fine – if unclassifiable – photographs . Trevor Winkfield had a further poem, and had elicited work from Meret Oppenheim and Harry Mathews. There was also the second part of the Vache letters – ‘…the whole tone of our action has yet to be decided – I’d like it to be dry, without literature, and, above all with no sense of ART.’ This time there were two interviews – one with Jean-Jacques Lebel, the other a group affair when we all went to London for a John Cage concert, and talked to him backstage. Both these had a socio-political turn which we were now attuned to. This after all was a time when it was impossible to ignore the Vietnam War- and its opposition. Together with material from Buckminster Fuller there was a distinctly anarchist strain.

Cage : ‘I would like to follow education with unemployment – so the idea would come into being of an unemployed country as something good….The revolution is killed by work, so the basic idea is to get rid of the notion of work…We also get rid of all sense of property . Instead of ownership, substitute use.’

Fuller : ‘…supposing we take away every politician, all the ideologies , all the books on politics – and send them into orbit around the sun. Everybody would keep on eating as before, down would go all the political barriers and we would begin to find ways in which we could send goods that were in great surplus in one place to another.’

Lebel: less fantastic, but equally radical, and angry, was also nicely virulent about ‘The future of the happening ?: Death by Madison Avenue. Death by Sorbonne, or Death by Museum. Dada ended by being buried this month in a lousy 3rd class cemetery: the Paris Museum of (so-called) Modern Art. This is how they castrate rebellions; they accept them. They buy them. They sanctify them.’

I think something of the radicalism of the period – its wildness, its anger, its dreaming shines through here, like a memory of childhood revisited on a grey day.

Around the same time – 1966 – I put together an exhibition -mainly photographic- entitled -‘Descent into the Street’. The title came from a Roland Penrose article, and recalled Breton’s statement, ‘Now I confess that I have passed like a madman through the slippery halls of museums …Outside the street prepared a thousand more real enchantments for me’. Its scope was wide – far too wide. What it did cover was that material already mentioned – Constructivist design, Dada and Surrealist actions; recent art that was not object based – the non-commodity i.e. such things as Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable; Chinese mass callisthenics – as well as – and this proved crucial to the future of the group and exhibition – Black Mask – the New York based militants and anti-artists, whom David and Anne Ryder had contacted and met in New York.

The fate of the show was somewhat odd; and in it’s way prophetic. In Newcastle it was housed in the University Physics Building. Then, courtesy of Ian Breakwell, it travelled to Bristol Arts Centre. Stuart and I went down to do another lecture / event – ‘People of the same bonfire’ – a Tretiakov title. Michael Kustow and Anthony Hill came to it with a view to it transferring to the ICA. But decided against it. It then went to Carlisle College of Art where the instigator – Mike Lyons – was sacked. It was not put up and I was left to collect it. Recuperation had yet to show don its masks.

But by this time, late ’67, the atmosphere had changed. The war had brought onto the streets an opposition that moved beyond the anti-war position towards the stirrings of a far more extensive opposition – a repudiation of Capitalism (how important it was that the system had now been named ) and ‘actually existing Socialism’. It was an intoxicating moment. One might not agree with other groups’ gaols, but at least we were, generally speaking, pushing against common obstacles..

The Wises were soon, if briefly, associated with Black Mask – then with the excluded English members of the Situationist International, soon to become ‘King Mob Echo’. I was certainly less of a radical than them; I still had to earn a living; I was still enmeshed in the art world (stamping books). While they were writing in Black Mask; ‘No artist can be anything other than the bedmate of the businessman and imperialist. Therefore it is not enough to institute a revolution of style and content (which only perpetuate the culture by giving it new blood): the culture itself must be destroyed’; I was carrying on the art historical thing, publishing in the October and November issues of Artforum a longish piece on “The Constructivist Ethos” to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the Russian revolution.

Through David and Stuart the S.I. made its way on to the Newcastle agenda; or rather it appeared like an avenging angel. My first taste was the London group’s translation of ‘The decline and fall of the ‘spectacular’ commodity economy’ – their defence and acclamation of the Watts Riots. It still reads like a text forged in a white hot crucible, here one could find a critique of the commodity, the notion of the Spectacle; the new definition of the proletariat -‘ those who have no control over their lives and know it’ etc. But there was also the poetic, the utopian, and the idea of ‘the transcendence of art and its re-entry into everyday life as play’.

Soon Vaneigem’s ‘Traite de savoir-vivre a l’usage des jeunes generations’ appeared in Chris Whitbread’ s translation. Here the repression of the everyday was stressed ,but also the transgressive, love, the imaginative, the poetic . Re-reading it today- it is clear why Debord was so easily incorporated into academia but not Vaneigem. (Though that process is now under way). I think it was that focus on the everyday that had an enormous attraction. If Debord describes a system, albeit all -pervasive and asphyxiating, Vaneigem focuses on the self that we have to push through this atmosphere , but also on the self’s release, its apotheosis .

Soon I was involved in the circulation of other Situationist texts – ‘Theses on The Commune’; ‘Captive Words’ etc, and the production of ‘pro-situ’ texts : An’ Interview with Brigitte Bardot’. etc. If, as is often claimed, the avant-garde (with notable exceptions) gravitated to one of two poles – the aesthetic, or the ideological, then the S.I appealed at that particular juncture for the very reason that it appeared to conflate those two, to unify them, to supercede them. Such an appeal was hard to resist. It was furthered by the fact that their texts were readable – eminently so.

Here too was a politics that was undeniably radical. If the earlier avant-gardes had found (or found and lost) their political affiliation with the Communist Party – such a position was now as unthinkable as affirming the parliamentary democracies sustaining capitalism. What the S.I. proposed – the Councils (and here there seemed an analogy with their view on the future of art) was – in its radicalism, its newness as well as the historical precedence – highly attractive. Here was the generalised road to autogestion. ‘All power to the Councils’ = ‘Poetry made by all’. If this, now, (as then), relies on slogans, then it seems worth rescuing the term from its derivative – sloganeering. Kristin Ross makes evident the value of the slogan:

‘A slogan might , in Alice Kaplan’s words, offer a particular condensed accounting for history, and “if the suggestion it offers is sufficiently powerful in the social sense of the term, it will be ,as it were, ‘present’ for the interpretation of the next historical event even as it happens.” In this way, she continues, “Interpretive form actually carries its effect into the real: history is telling and making at once.” Rimbaud’s “presence” in May 1968, as libidinal precursor, as slogan (“Changer la vie”), his “presence” before that, for the Surrealists….this presence is not so much the inheritance of a “thing” or an artistic monument as the embracing of a situation, a posture in the world: the conditions for community, the invention or dream of new social relations. What is transmitted is not a solitary, reified literary monument but rather the often prescient strategies that constructed and mobilized it…. The force of an idea lies primarily in its ability to be displaced’(1)

Icteric was behind us. But not, for me, the history that had so fascinated us. I was given the opportunity to pull together some of those threads; to try to make something a bit more coherent than ‘Descent into the Street’ through the auspices of Pontus Hulten at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. As a result of the ‘Contructivist Ethos’ piece he had asked me if I would like to curate a show based around Constructivist theatre and film. I had worked on it for a while when May ‘68 erupted. Here was a transformed Paris – factories and patisseries with the ‘Occupe’ sign; students interviewed on British television correcting reporters – ‘No, we don’t want to seize power. We want to destroy it’. From the graffiti it was clear the S.I. were a highly active presence: ‘Under the paving stones – the beach’. ‘Culture is the inversion of life’. I could not ignore such an extraordinary moment. I suggested to Hulten I change direction and do another version of ‘Descent into the street’ -entitled – ‘Poetry must be made by all/Transform the World’ and he readily agreed.(Fig 4) This was to be a version of ‘Descent into the Sreet’ that omitted the non-revolutionary elements of that show, and showed the May ‘evenements’ as a kind of summation. May ‘68 seemed to show that what had once been the delirious outpourings of elite and obscure groups of artists was capable of becoming the property of the – temporarily enlightened – masses; it could be appropriated by the many – the fulfilment of a promise present in Dada, early Surrealism and Constructivism and currently proposed by the S.I. The promise of a’ lunatic poetry’ triumphing over a vanquished ‘survival.’

Again it was largely photographic, and again I drew on the resources of the Fine Art Department. David Wise’s version of Malevich’s coffin was part of it; so too was a reconstruction of Tatlin’s glider in a version for a six year old child made by Roger Fulcher ( See Fig. 5). Stuart Wise made a series of photomontages based on the Surrealists suggestions for the ‘ embellishment’ of Paris’ (Fig.6). The documentation started with material from the 20’s taken from Gregory Bateson’s book – ‘Naven’ which documented everyday ceremonies among the Iatmul of New Guinea . This I still see as a near absolute – a peak in the idea of lived poetry. It then moved through the Russians, Dada, Surrealism, (and the Marx Brothers), to the May phenomenon. I avoided reference to the Situationists (though much of the graffiti was theirs) for two reasons – principally because I had no wish to be a recuperateur; secondly I found most of the theory I needed in Marcuse. Here was a Marxism shot through with modernism and its critique, that once again recognised the importance of the quotidian.

I tried to set out the theme of the show in the catalogue introduction:

“The title of this exhibition is taken from Lautreamont and Marx respectively; it indicates the basic themes and links radical art and revolutionary politics. With this union the traditional notion of art often seems to disappear, and the concept of politics take on an added dimension….

One of the recorded slogans of the May revolution in France last year read “1936 – derniere couche de peinture”. In seizing the means of communication as best as it could – and this it did most successfully – millions were aware of the wall slogans – the revolutionaries made it clear by the very nature of the slogans that this was a new type of revolutionary situation. Lenin’s definition – ‘Revolution is the festival of the oppressed’ was near to realisation. Poetry had come to the streets again. The Commune reborn, not in the form, but in the spirit of 1871 when a similar creative force had appeared. In Russia when the revolution was young poetry had manifested itself there – on the streets. When, following the suppression of the May events, one can read journalists of the bourgeois press lamenting the disappearance of ‘ a poetic quality of life’ then one can be doubly sure that poetry had passed from form to matter.

This exhibition is concerned with certain themes related to that slogan “1936…” For many ‘primitive’ societies painting, poetry, etc. have no such life-span, as forms they had never in effect existed. The fantastic poetry of the `Naven’ for example is part of a natural environment, everyone’s environment. At the time when one might have witnessed the Naven ceremonies one might also have heard individuals in Russia declaring that art had outlived its usefulness – ‘the collective art of the future is collective life’. In France Dada had attempted to assassinate culture. Surrealism following in the wake had proposed a new non-repressive reality principle, one accessible to all – “Surrealism is within the compass of every subconscious.” These things have a similar and essential core – the non-hierarchical classless society.”

Like ‘Descent into the street’ it focussed mainly on the achieved, the realised – much of it from ‘20s U.S.S.R; rather than the ‘to-be-realised’. And here was the difference with the S.I. Their heritage – in cultural terms – was European; the transcendence of art was a goal. This was always expressed in Hegelian terms of suppression and realization. . For my part, the Russian avant-garde was vitally important. It seemed – if one focussed on the cultural scene – as if something Utopic had, for a brief moment , come near to realisation. Here were prefigurations of the transcendence of art .The S.I seemed preoccupied with the heritage of Dada and Surrealism, and saw these in Debord’s memorable – if debatable – phrase as having tried to ‘suppress art without realising it’ (Dada), or’ realise art without art suppressing it ‘(Surrealism). One suspects that the Russian avant-garde were seen as tainted with that bete noir of the S. I. – Leninism.

The exhibition opened in Stockholm in late ’69 (Fig.5). And there it was deemed a success – thousands of visitors on the first day alone. (Some twenty odd years later I read in Flash Art someone praising it as the Museet’s most important exhibition in 25 years). Hulten had invited other groups to use the space – so there was the presence of Black Panther exiles etc. As Hulten put it ‘Questions were asked in Parliament’ ; but no more. From there it went to Munich, where the reaction was different . Following Hulten’s lead the Kunstverein had invited students to respond – they had – the authorities disapproved – they were evicted and Stockholm closed it in protest. The ICA wanted it in London – but this time it was my (foolish?) turn to say ‘No’. I had a real reluctance to enter the English art establishment. (Hence there were very few copies of the catalogue in circulation. Fig.(4) (Icteric too never found its way into the Institutions; we distributed it mainly by personal contact – our target audience being disaffected art students.)

By 1972 in the depressing and repressive atmosphere of the time I was glad to move on and accept a visiting post at UBC, Vancouver. There – not by my instigation – the show opened at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 1973. (I was then on a Guggenheim Fellowship trying to sort out the theory of ‘The Transcendence of Art’.). Had I been asked I might have been wary of the wisdom of showing it in Vancouver – then very much a laid back place. As it was, it went virtually unnoticed. Given that, I was surprised some years later to learn that from Vancouver it went to another venue in Canada (Alberta I believe), where the institution decided against mounting it, and furthermore refused to return it to Stockholm. Plus ca change.

Soon the ’68 evenements’ were a memory. The S. I. had reached their apotheosis then, now it was their ‘decline and fall’ time. In a decade or so, Lebel’s words were to sound all too prescient:’ Death by Museum, Death by Sorbonne’. Throughout the dark ages of the seventies (little did we realise how long the ‘restoration’ would last) I continued to push the S.I and their antecedents (to little effect); by the end of the 80’s there was no such need: the S.I were wholly incorporated, and a decade and a half later their availability and emasculation continues. My local University Art and Design library has 12 copies of ‘The Society of the Spectacle’. Even ‘King Mob’ is part of the cultural scene – its magazine turning up in Maggs Bros, Antiquarian booksellers of Berkeley Square. The 20’s vanguards etc are almost completely the preserve of academia.

The Stockholm catalogue has long been out of print .But not completely forgotten – Liam Gillick has made a work based on it; as has Christopher Williams. I don’t know either piece, but suspect they both belong to that ‘failed utopia’ genre that has enjoyed some vogue recently. For my part – the failure is not the point. I still see the space explored by the Stockholm show as worth visiting. And, given the exponential growth of the modern art history industry I am surprised it has not warranted such effort.

Has it any relevance today? In the context of globalisation, obscenely increasing inequality; looming ecological disasters, the miserabilism of Western politics, and the sheer amount of the ‘unbelievable’, that is daily heaped before us; then it may well seem irrelevant, Indeed the idea of creating ‘a situation from which all turning back is impossible’ seems irrelevant and impossible. If it has any relevance at all then it must lie in the context of an institutionalized art world. An art world I see as pervaded by a clamorous banality; one rapidly collapsing into the arena of a degraded popular culture; where a modernism that strives to keep alive the age of the heroic can only survive on the back of a rampant commercialism, fighting, a rearguard action.

But this world too has its fissures, its malcontents. And like Wilde I believe that the utopic and, perhaps more importantly, its harbingers still have their value and place. In the Stockholm show I tried to map a space where the everyday was the focus. An everyday that is at one level a source of massive oppression; but which we know can be transformed, into something liberatory, poetic, savage and beautiful – even if we know that this has happened very rarely and very briefly; an everyday in which perception is no longer on ‘automatic’. A space that can encompass not only Blue Blouse but Cravan, not only the Visit to St Julien le Pauvre, but ceremonies like those of the Iatmul, a space for the Vkhutemas and a film like L’ age d’Or, all these in their new manifestations – a place to which dialogue has returned . History – one would like to think- is not only a nightmare, but, a source of hope. In a time when, for many, such hope seems, if not extinguished, then very fitful in its appearance ,it might just have some illustrative role; point to a site where hope has flowered. Even if that seems even more ridiculous now than it did 40 years ago.

If the avant-garde is dead, through recuperation/institutionalisation or a mtetamorphosis into a postmodern, (which may be a mutated modernism) , ‘where everything verges towards exposure, publicity, the spectacle, interpretation and surveillance’; where do some of its one time members act ? We have all moved on, inevitably three of us entered the mainstream. Trevor Winkfield is an established writer and painter in New York. John Myers works, as I did, in that very institution we came to vehemently reject – the art school. David and Stuart Wise however have kept their radicalism – they have used their considerable artisanal skill as plasterers. They still publish tracts; make films on butterflies .On their website – Dialectical Butterflies one can find their radical re-reading of Mallarme, the English romantics, Marx and Hegel etc. recontextualising the present ecological crisis : and thus keeping alive the dialectic – as well as the Dada and Surrealist tradition of vituperation. Tate Britain recently acquiring their archive refers to them as ’near mythical’

The forgoing might be seen as some form of ‘discourse on resistance’ as Paul Mann describes Hal Foster’s essay ‘Subversive signs’ and the work it presents i.e Barbara Kruger’s etc., but Mann goes on to point out that such is the nature of discourse around the ‘critical’ that Foster’s work really amounts to ‘a publicity campaign’. If this applies here, as it well might, then at least a 40year hiatus might be invoked to some mediating effect.

Ron Hunt